When the screen flickers to life, so, too, does Seth Godin. A thin smile creases his face, framed by the colorful eyeglasses that have come to be known as the author’s most familiar physical trademark. “Pleasure to be here,” he says upon joining our video chat. “Pleasure to be anywhere.”

In fact, this is more than a pleasantry. Godin is not used to being merely anywhere, because he is most often found everywhere. He is the writer behind more than 20 books, many of them best-sellers. He is the speaker featured on countless Ted stages, his talks viewed by the millions on YouTube. He is a former Yahoo! executive, top blogger and podcaster, and, as of 2018, member of the American Marketing Association’s Hall of Fame.

Godin’s 2008 book Tribes: We Need You To Lead Us has long been established as a seminal piece on leadership. From his workspace near Manhattan, Godin revisits Tribes, how its lessons apply to companies navigating new, uncertain realities in business, the most important things leaders must do in times of crisis, and how to run an effective video meeting. “I did a Zoom training last week,” Godin says. “One guy showed up without a shirt on. It's like, ‘You wouldn't do that in real life. What are you doing?’"

(This interview has been edited and condensed for clarity.)

For those who haven't read your book, what is the abridged version of what a tribe is?

Godin: A tribe is a group of people who share a direction. Maybe it's a culture. Maybe it's a uniform. Maybe it's a way of being. They probably have a leader. It's really unlikely you have a tribe. I don't have a tribe.

A tribe could be everything from the kind of people who go to science fiction conventions, to the kind of people who become entrepreneurs, to the kind of people who keep track of how fast their cars drive. Tribal behavior is a fundamental human enterprise, and if you ignore that and try to talk to everyone, you're probably talking to no one.

How does the idea of leadership come into play with a tribe? How does a leader emerge in a tribe?

Godin: So let's be really clear: Leaders and managers are different things. Management needs authority. Management is what happens when you get to tell other people what to do. We need managers, otherwise we'd have no fast food, we'd have no Tim Hortons. We'd have lots of things missing from our world.

But leadership is voluntary. It's voluntary in the sense that no one has to follow you, and you don't have to lead. Leadership involves saying, "We're going to go over there. I'm not sure it's going to work. I'm not sure how we're going to get there. Do you [still] want to come?"

And that is how tribes choose to move forward. You don't have any authority when you are leading a tribe, but you do, perhaps, have a voice. You can say this key sentence, which is one of my contributions to the world: "People like us do things like this. Members of this tribe do things like this. [They] follow this path."

So we can go down this long list of fast-growing or important organizations that got there because they don't say to the whole world, but they say to a tribe: "You're one of us, and this is where we are going."

Let's stick on that tact for a minute, because I think in this new reality of the way people are doing business and working together, perhaps companies are struggling with how to maintain leadership—not just management.

What are the most important things that a leader of a tribe must do in a time of crisis?

Godin: The word “crisis” has been misused by the media. A crisis, like the Cuban Missile Crisis, has an ending to it. You are on high alert, and then you're not. Changes in the culture as we know it are not crises, they are chronic conditions. And chronic conditions demand chronic solutions.

So if you're in a crisis, you need to do a few things. You need to be able to see people because they want to be seen—they feel disconnected and they feel alone. Second: What we count on from our leaders is not that you act like a toddler, not that you have a tantrum, and not that you are impatient.

What we ask for from our leaders is: Can you see the world in a slightly longer view than we're inclined to do so? Because leaders [understand how to instill] stability, and they need to use that to help us go to the next level.

What we have to do as leaders is figure out what our chronic solution is. How will we choose to model behavior for the long-haul? Because it's going to be a slog, and acting like it's not going to be a slog is a mistake.

In Tribes, you note that a group needs only two things to become a tribe: a shared interest and a way to communicate.

If I'm a company that doesn't necessarily have a shared interest—I have, in essence, a couple of people at the top, who have profit at the center of decision making, and a bunch of people that work for me—is there a new opportunity to create that intent, to create that shared interest because of the greater world circumstances right now?

Godin: You totally nailed that. There's a new opportunity to do it every day. What is the purpose of a Zoom call? If the purpose of the Zoom call is to take attendance—make sure that no one is taking the day off, get people to comply, and show that you have power—well, then you've really established what kind of organization this is.

If you cancel the Zoom call and send everyone a memo about what they needed to hear, and then do one-on-one conversations that go deep into what this person's contribution [is] going to be, people will feel seen and [things] will change. This is a choice. It's a choice that every manager makes every day. The choice to be a leader instead of a manager.

How do companies not make a time like this, where most people are more physically segmented than they ever have been, a time when we turn back into individual crowds and lose that sense of tribe?

Godin: I think what it comes down to is: What's the dynamic of your organization? Is it a hierarchy? Is it a studio? Are people making promises to one another? I'm really fortunate. I work with seven extraordinary people. When we suspended operations three weeks ago and everyone started working from home, our output hasn't changed one bit. Because we don't depend on someone handing a memo to someone else and then down the chain. We depend on making promises to each other.

Companies for a long time bragged about how many employees they had, because kings brag about how many subjects they have. But going forward I think we're going to see organizations bragging about how few employees they have. Those people who are insiders, you need to treat them like insiders, or you can't expect that they're going to act like the community that you're hoping for.

Do you have the sense that some larger companies may begin to trim down staff with the idea that it won’t actually hamper their efficiency?

Godin: Well, I certainly didn't invent any of this. I mean, Tom Peters has been writing about it since I was 22. If you look at what they did at W.L. Gore, the people who make GORE-TEX, every time one of their facilities got to more than 150 people, he would split the team and they'd have to open a new office.

There is no office W.L. Gore had with more than 150 people in it, because [they] knew that’s the maximum size for an organic tribe.

There's one other idea in Tribes where you explain Kevin Kelly's riff that you need only about 1,000 true fans to become successful. These are the people that, if you're a musician or somebody like that, they'll travel for miles to see you, they'll wait in line to buy your stuff. They're the people that are the most loyal and devoted, and will very much help with the heavy lifting involved in spreading your message.

If I'm a company leader, how does that translate? How many people do I need spreading my message within a company to kind of have that similar effect?

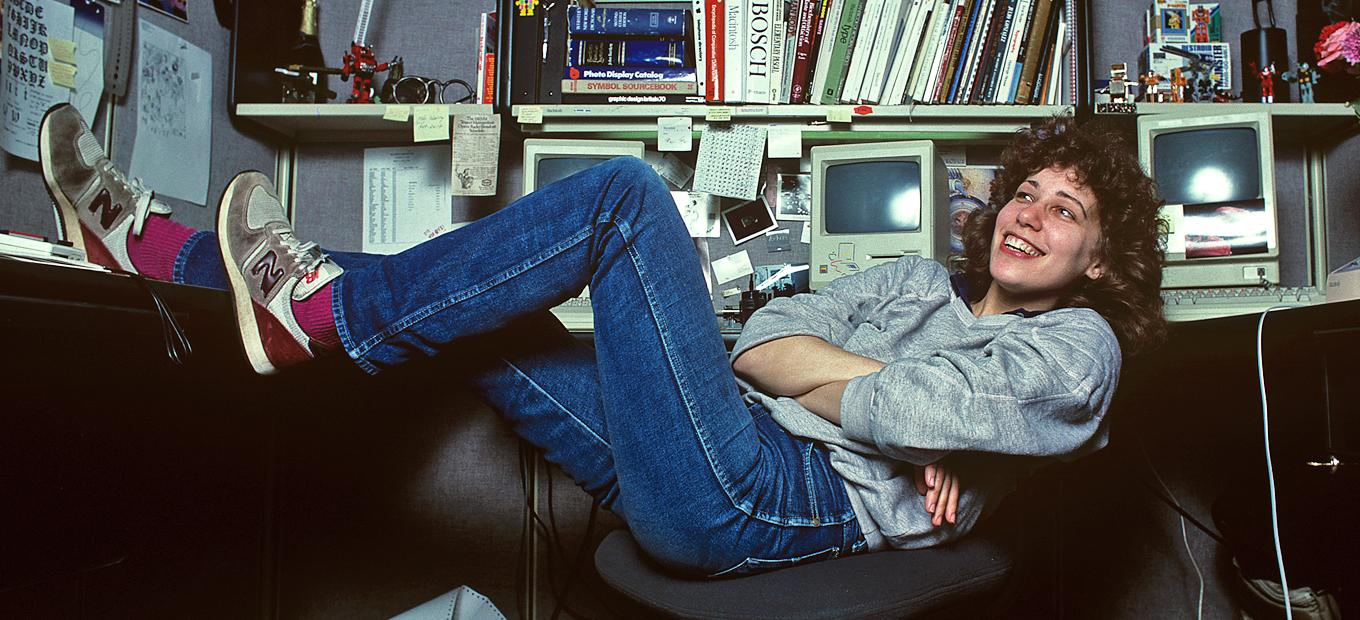

Godin: What does it take internally in an organization as a leader [to have true fans]? Apple maybe had, at its peak, 1,000 people who would turn down a much better job to stay there because they were part of what that place was. When you talk to Susan Kare (pictured below) 30 years later, she still remembers the experience that the Mac was built by 13 people—13, that's it. So you don't need that many at all.

But most CEOs I know don't have any [true fans]. If they have a few, it would be amazing. And [CEOs] think they can buy them. People are not for sale—that's not how you get them. You get them by showing up for them in a way that makes them believe that their life is better if they show up for you.

What do you tell people when they ask, "How do I achieve fans within my own company, among my own leadership?"

Godin: I'm not sure anyone's ever asked me that, actually. I guess what I would say is: Why?

If you're telling me you want to achieve [fans] so you'll make more money, then I would say you should probably go run a factory instead. But if you're telling me you want to do it because you feel a calling to see and connect and lead people, then you're probably already doing it.

The hard work is deciding why you want to do that in the first place.

In a time like this, of general unease about what the world is going to look like in the short-, medium-, and long-term, is this an opportunity for new leaders to spring up where they wouldn't have otherwise done so?

Godin: Well, I'll just remind people that Google and Shopify both came out of the dot-com bust. In fact, just about every important organization comes during a time of bust.

During a time of boom, the market leaders, the tribal leaders—the leaders of every stripe have all the advantages.

But in a bust, they're suffering because they're trying hard to maintain the status quo. And so, if we look at Zoom—their traffic is up 20x in the last month. They didn't wish for this to happen. But suddenly there's a new important software company on the horizon.

As an individual, the question is: Will you build something that's optimized for the year 2018, or will you build something that's optimized for the year 2021? If you want something for 2021, now would be a really good place to start.

Tribes was published in 2008. Now, certainly most of the work that went into that book was done before the recession hit. But I'm curious about the role an economic collapse had on leadership at that time as you saw it.

Godin: We had a bit of clarity for a little while that leadership and money weren't the same thing. We saw people like Jack Welch called out as the fraud he was. And suddenly, [when] he wasn't making as much money, everyone said, "Oh, he must not be a leader anymore."

Those things aren't the same thing. Looking at the Forbes 400 as an indicator of anybody's skill is probably a mistake. So in this new cataclysmic moment, I think we're going to need to ask ourselves the simple question of: Who would miss you if [they] were gone?

Because there are lots of things that are going to be gone [in a recession]. And if they're not going to be missed, well, that's probably good riddance. But if you do something that's important to people, they might find a way to help you persist.

You've prefaced my natural followup, which is something of an unpleasant one. As we stare down the barrel at another looming recession, it's been 12 years now since the last one began. What do you imagine will be different in terms of tribes and leadership as we head into a possible recession in 2020?

Godin: Well, first, there's no doubt there's going to be a recession. I think there's a wonder if it's going to be a depression. I hope not. Are you playing a game that depends on basis points and making money, or are you focused on how you can be of use to people?

Because there's never been a time we've needed your help being of use to people more than right this minute. So instead of worrying about macro trends, I think, find your smallest viable audience. Ten people, 500 people, 50,000 people, and be of service to them. That will be enough.

You're of course known as an author and a speaker, but you have plenty of direct corporate leadership experience yourself—most notably, as a vice president for Yahoo! (author’s note: Godin served as the web giant’s VP of direct marketing from 1998-2000.) Do you have a sense how you might be approaching leading a company team in a time like this?

Godin: In organizations of scale, people want reassurance. Investors want reassurance, employees want reassurance. [But] uncomfortable as it may be: Reassurance is futile. There is never enough reassurance. You can't keep telling people everything is going to be okay because, by their definition, it's already not okay.

What you can do is say, "We have a plan for right now, and we're going to replace it with an even better plan as we get smarter." And: "Resilience is what we're going to focus on, and there's going to be shared sacrifice, and we have a chance to make things better." Because that's all true, and leading with truth is really powerful because you don't have to keep checking your story. You can simply describe where you are and where you're going, and use that to help others help you move it forward.

You run your own course called altMBA. It's this four-week intensive online workshop that's turned out executive alumni from companies like Nike, Coca-Cola, Google, IBM, LinkedIn...the list goes on.

Either from your own presumptions or from first-hand talks you've had with people at these companies, what are they going through right now? What are their unique considerations at a time when workplace functionality has likely never been more different?

Godin: What we are hearing over and over again, with 4,500 graduates around the world, is people work in organizations where all these skills are scarce. They work in organizations where people have done the spreadsheets, where people have the easily measured skills, and where people go to meetings six or seven hours a day to avoid taking responsibility.

And [that] can be replaced. It can be replaced by people taking responsibility and not waiting for authority, and [by] people who choose to lead. What we found is, if you show up like that at work, you're either going to get promoted or someone's going to hire you away because this is the scarce resource of our future. In uncertain times, what we value the most are people who know how to be resilient.

Let's finish here with some talk about the Zoom call or the video chat. You have been an outspoken chronicler on your blog about appropriate video chat etiquette and appropriate video chat behavior.

I have not exactly split the atom here by suggesting that the video chat is now going to be something companies rely on even more heavily than they have in the past. Can you give us a look into your go-to rules for a productive Zoom meeting or video chat?

Godin: Well, the most important one is to cancel it. If you are simply trying to deliver information, you should send an email. You should even record a video and send it to people to watch in their spare time.

If you're not going to cancel it, that's because it's a conversation. And if there's more than four people on the call, you can't have a conversation. So, therefore, you have to have breakout rooms. You have to have a posture that says, "We're here to do something right now. We're going to get it done as quickly as we can and then go on to the next thing. The thing we're going to do is, we're going to make a decision. We're going to learn to understand something, we're going to surface misunderstandings, and then we're going to move forward.”

And we have a meeting hygiene problem. I did a Zoom training last week. One guy showed up without a shirt on. It's like, "You wouldn't do that in real life. What are you doing?" Don't eat on the call. Make sure you don't have backlighting.

There's so many simple steps to take to present yourself the way you [should] present yourself. If it's important enough to have the meeting, it's important enough to do it well.

If I'm the one who has called a meeting, what should be my appropriate rules of engagement? What level of expectations should I set, or what are the things that I absolutely must accomplish for any video call to achieve max effectiveness?

Godin: They're all different. It's like [how] there are no rules for what makes a good email. There are just rules to what makes a bad one.

But here's what I have found. One: Multitasking works really well in a digital setting because you have a chat window. Using the chat window for people to contribute, before it's their turn to talk, is really helpful.

Number two is: The Amazon method of everyone reading the memo before the meeting starts, or as part of the meeting, is really strong. Because if you don't have a memo, don't call a meeting. If you don't have something we're trying to decide, don't call the meeting. What's this for? Be really clear about that.

And number three is: Someone should be in charge and someone should call on people. This whole idea of “come off mute when you have something to say” just leads to all these people hesitating to come off mute. Whereas, if it's “type in the chat if you've got something to say and I'll call on you”—if you gave me a good hint [that you want to speak]—now someone is leading the thing.

At Harvard Business School, [when] they do a case study class, the professor doesn't just sit in the corner waiting for people to talk to her. She calls on people. She drives the conversation forward. It's a skill. And so is running a Zoom meeting.

The idea of FaceTime or Skype or Zoom is certainly nothing new. But I think you could clearly make the case that—at least in terms of the business world at large—we are perhaps still in the early days of the video chat being relied upon for quite literally every personal interaction between colleagues at work.

You blogged about this idea on Mar. 18. You said, "We have a chance to reinvent the default and make it better." What direction do you think the video chat takes as more innovation comes into play—as we have an even greater need to improve this medium that is very much having its moment right now?

Godin: I think [video meetings] should get longer or shorter. If I have five minutes to talk to Jason, I'll use it well. Whereas, if we have to fill in time because we have to spend an hour, it will get worse.

On the other hand, if I have a four-hour coworking session, where five of us are all on-screen doing our work on our laptop and someone has a notion and they speak up, it's like we're in the office together again.

If I say, "Oh, I got to start checking my email"—that would be rude in [a five-minute] call because we have a very specific function. But, if we were on all day, it'd be different.

Read more

- Jungalow's Justina Blakeney on Using Social Media to Support Social Movements

- Daymond John on Bombas, TikTok, and the ‘Shark Tank’ Deal That Got Away

- Ross Bailey on Moving IRL Online, and What Retail’s Comeback Will Look Like

- Dave Gilboa on Seeking More Retail Space (Not Less), and Reopening Warby Parker

- Hugo Engel on Leon’s COVID-19 Pivot with Feed Britain and How Restaurants Can Embrace Technology

- Tamara Mellon On the New Luxury, and Why the Days of Brands Staying Neutral Are Over